Rapid7 software engineer Eliran Alon also contributed to this post.

Introduction

Despite sustained efforts by the global banking and payments industry, credit card fraud continues to affect consumers and organizations on a large scale. Underground “dump shops” play a central role in this activity, selling stolen credit and debit card data to criminals who use it to conduct unauthorized transactions and broader fraud campaigns. Rather than fading under increased scrutiny, this illicit trade has evolved into a structured, service-like economy that mirrors legitimate online marketplaces in both scale and sophistication.

This evolution has given rise to what can be described as carding-as-a-service (CaaS): a resilient underground market that wraps together stolen payment card data, tools, and support into easily accessible offerings. These stolen credit cards are also often bundled with sensitive personal information, substantially elevating the potential damage to both individuals and organizations, and making the financial loss the least harmful consequence.

While numerous dump shops have been disrupted or shut down over time, several high-profile marketplaces, including Findsome, UltimateShop, and Brian’s Club, continue to shape the market and influence criminal activity. This blog explores these illegal marketplaces and their operations, shedding light on the modern carding economy and highlighting why stronger detection and prevention efforts remain critical.

The carding economy at a glance

Credit card information available on the black market is generally categorized into three types: credit card numbers, dumps, and ‘fullz’.

-

Credit card numbers (also known as “CVV”) minimally include the data printed on the card: the credit card number itself, cardholder name, expiration date, and the CCV2 security code (found on the back, not to be confused with CVV). This group may also include the associated billing address and phone number.

-

Dumps consist of the raw data from the magnetic stripe tracks. This information is essential for cloning physical credit cards.

-

Fullz offers a more complete profile of the cardholder, containing additional personal information such as the date of birth or Social Security Number (SSN).

The exact origin of the information available on the different marketplaces is unclear and is being obfuscated by the admins and resellers; however, further investigation across different cybercrime forums revealed the common methods through which cards get leaked.

Phishing

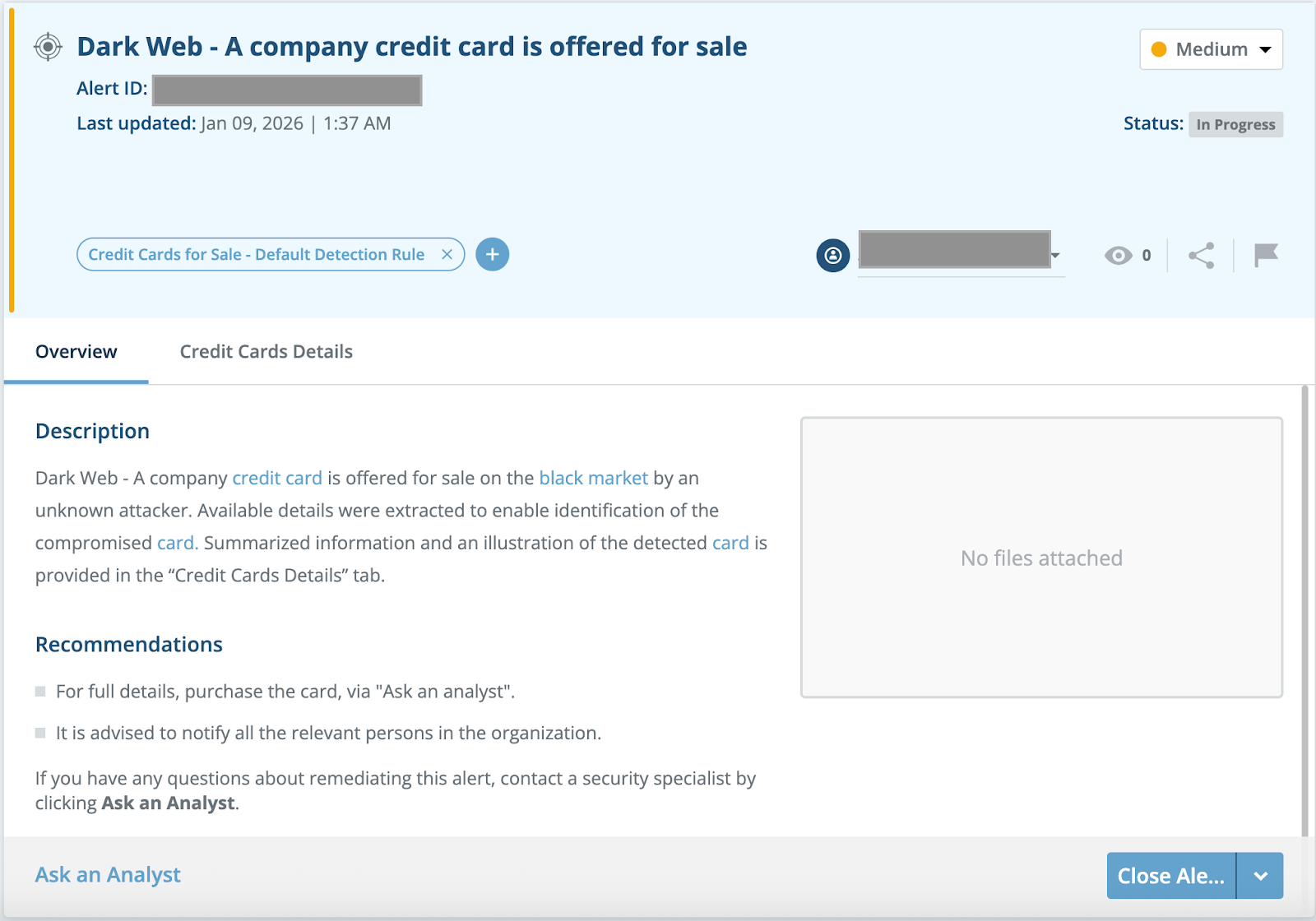

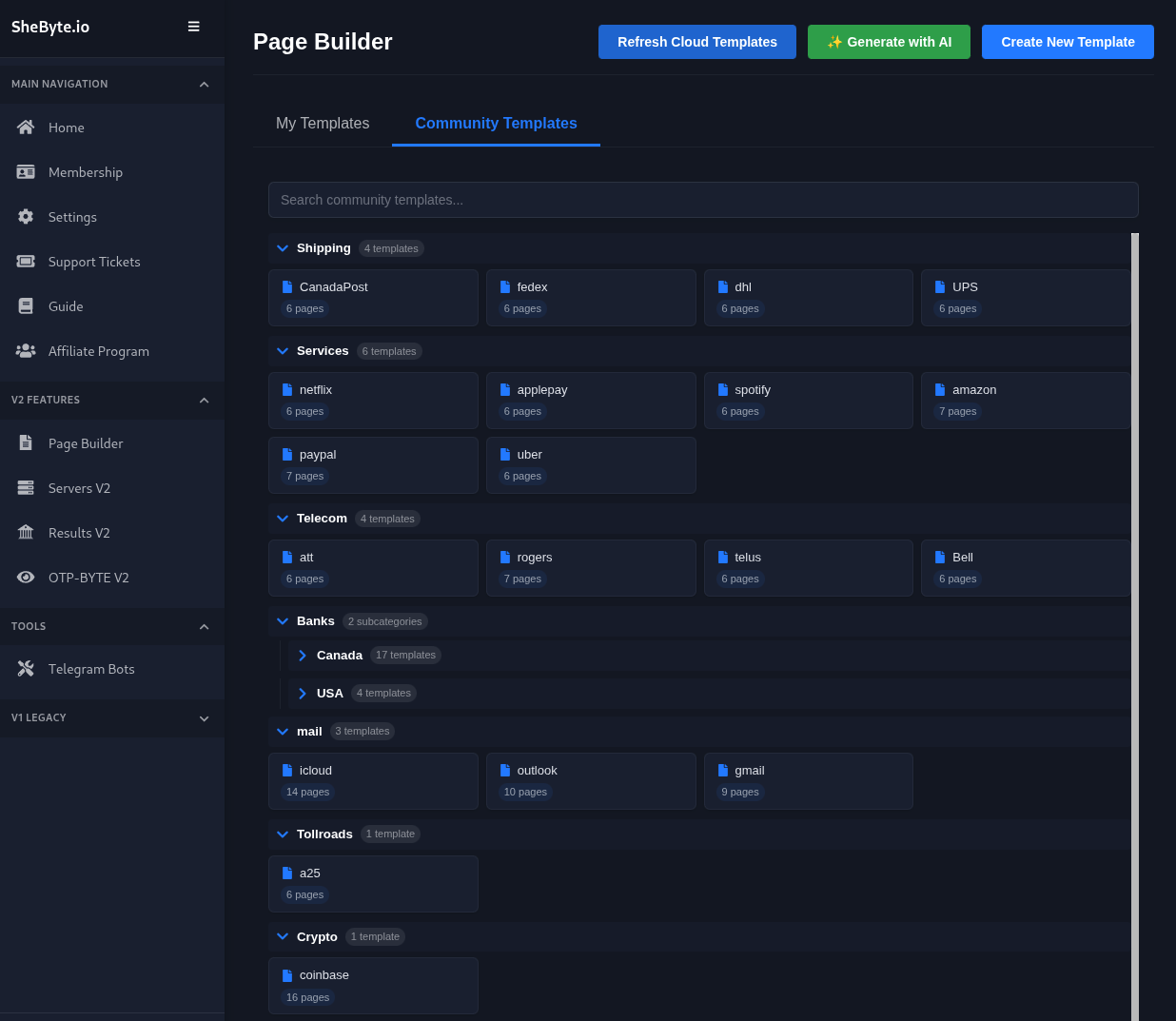

Technological improvements have made phishing campaigns much easier to execute. Today, there are phishing-as-a-service (PhaaS) platforms and fraud-as-a-service (FaaS) modules allowing easy setup for new phishing campaigns, along with the infrastructure, page design, and even the collection of credentials or other stolen information (Figure 1). Phishing pages, tricking customers into providing personal financial information (PFI), are still an efficient source for stolen credit information.

⠀

Physical Devices

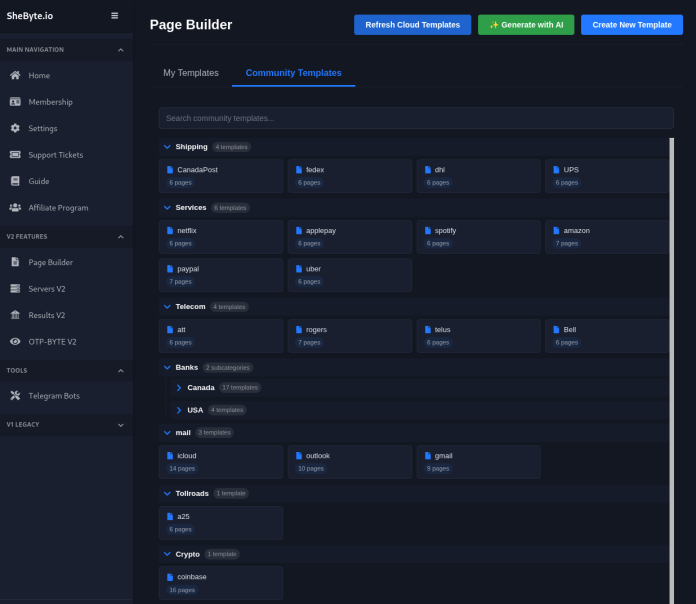

Physical hacking tools, and other devices that could be attached to different payment devices or ATMs, are used to transmit information into the hands of a malicious actor. Different specialized stores offer to sell such devices and ship them, once again allowing even a novice to start stealing credit information for future use. Threat actors attempt to stay as up-to-date as possible, adjusting themselves to industry trends. These include “Shimming,” which focuses on modern EMV chips, instead of old “Skimming” devices, which require scanning the entire card (Figure 2). The hacking tools target not only ATMs, but also additional devices with daily credit card use, including gas pumps and point-of-sale (POS) machines.

⠀

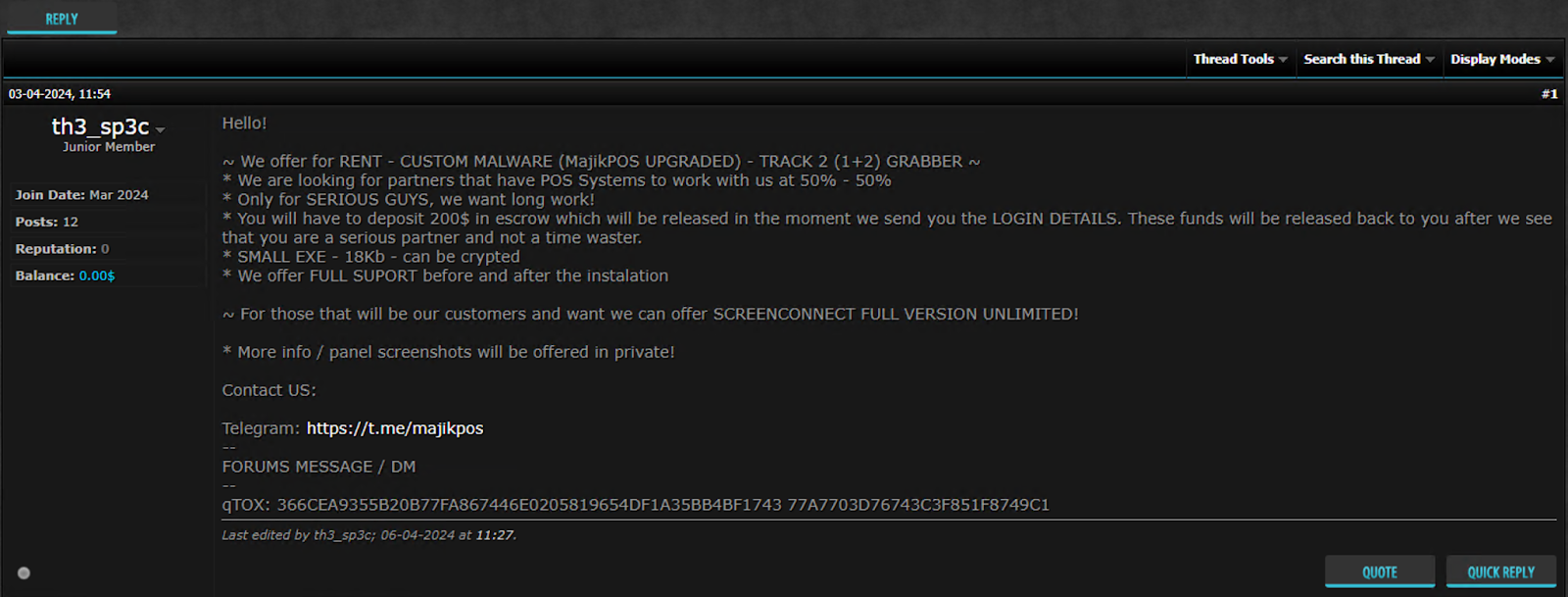

Malware

Since the large-scale Target breach in 2013, which resulted in the compromise of millions of credit card records, threat actors have steadily evolved point-of-sale (POS) malware variants such as BlackPOS and MajikPOS (Figure 3). In parallel, the widespread adoption of information-stealing malware (“infostealers”) has enabled attackers to harvest credit card data from a broad range of systems, typically alongside additional personally identifiable information (PII) and user credentials.

⠀

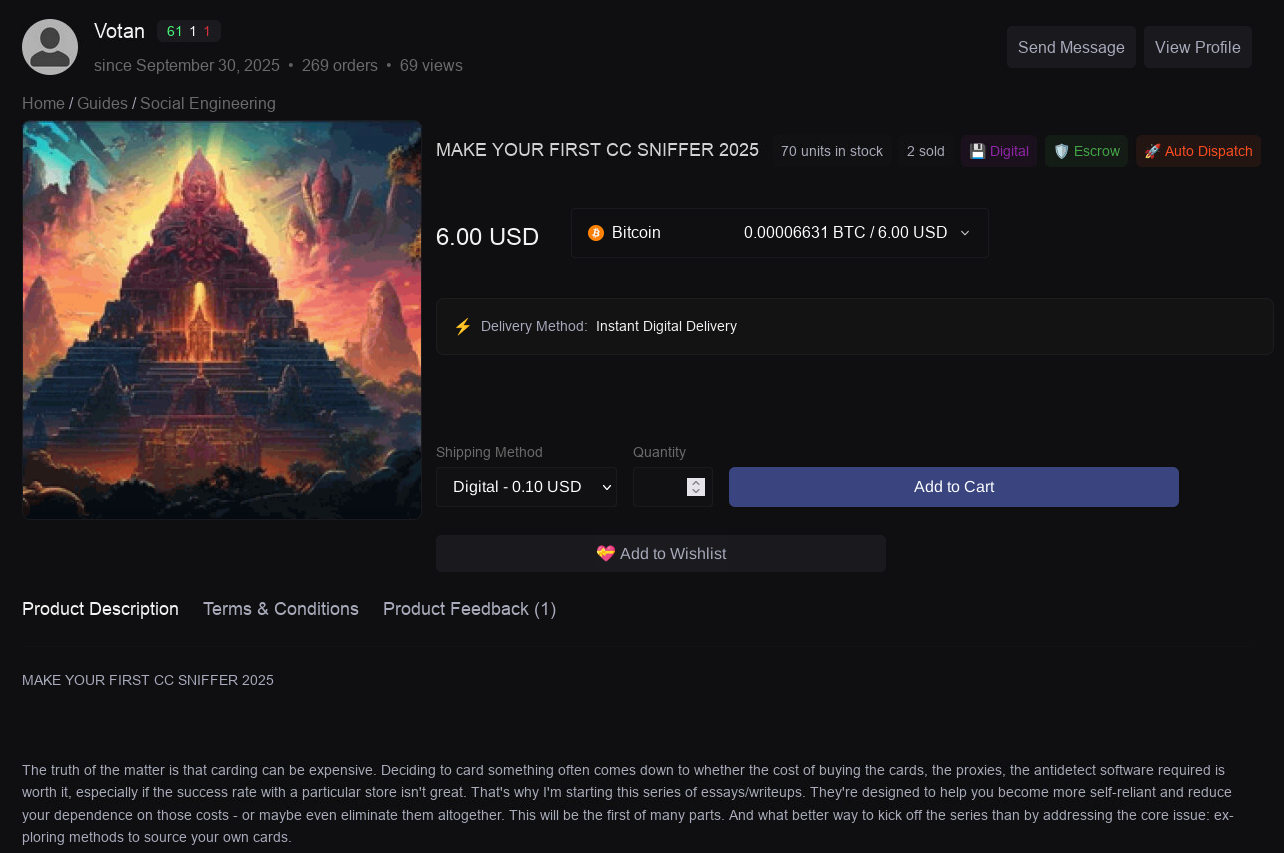

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Many posts found on different cybercrime forums provide carders with tips about how to exploit web security flaws. In some cases, there are actual examples and guides, including code samples for conducting XSS, i.e., redirecting network traffic into the threat actor’s hands through an injected code (usually JavaScript). Malicious actors inject the “sniffer” in the payment page itself, which later copies the inserted payment information and transfers it to them for future use (Figure 4).

⠀

Key players in the carding underground

Through ongoing changes within the carding ecosystem and the developments made in fraud detection and prevention, the industry of stolen credit card trading continues to flourish. Banks and credit card companies might be fairly good at monitoring individual transactions, but not at disrupting the broader fraud supply chain. CaaS exploits gaps between payment security, identity security, and organizational visibility, monetizing stolen data upstream before fraud ever reaches issuer models. In addition, fraudsters feed on the ever-lasting weakness of the human factor, acting carelessly with personal information and ignoring security warnings.

These factors, in conjunction with constant market demand, have kept several carding marketplaces, led by Findsome, UltimateShop, and Brian’s Club, in action for a lengthy period. While the design and branding of these marketplaces differ, their core offerings and functionality are largely similar. As a result, their administrators frequently promote their services across dedicated carding marketplaces and broader cybercrime communities.

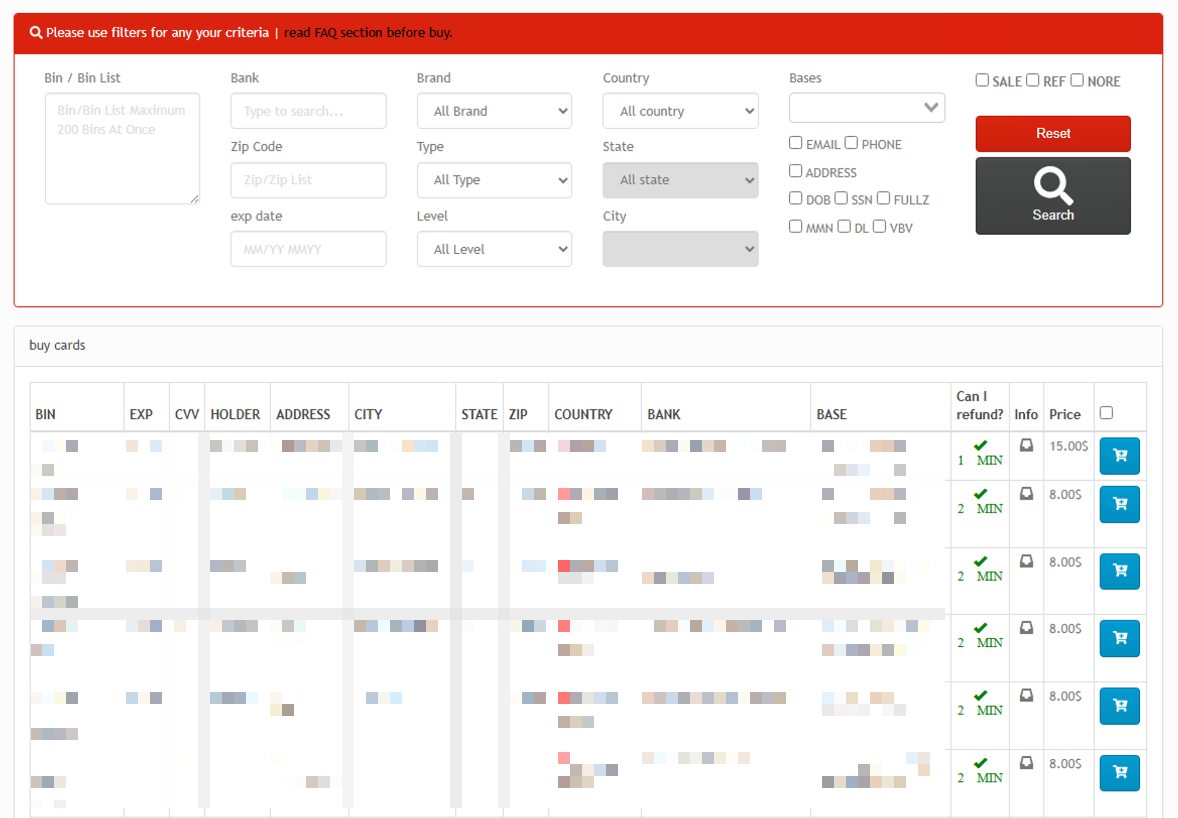

The main interface of these marketplaces features a streamlined search function that allows users to filter available listings using several parameters, including Bank Identification Number (BIN), country, and “base” – a collection of card records linked to the same issuing bank, card brand (e.g., Visa or Mastercard), and card type, typically compromised within a similar time frame. Filtering options vary slightly between platforms and may include additional criteria such as price range or the availability of supplemental PII, including SSNs.

Search results generally display the card’s expiration date, issuing bank, cardholder name, and approximate geographic location. Each listing also indicates its price and whether it is eligible for a refund. Refund functionality is a critical feature in the carding ecosystem, as it enables buyers to recover funds for cards that later prove invalid. This capability often serves as a differentiating factor between marketplaces, as user complaints on carding marketplaces frequently center on invalid cards, denied refunds, or the resale of outdated card data.

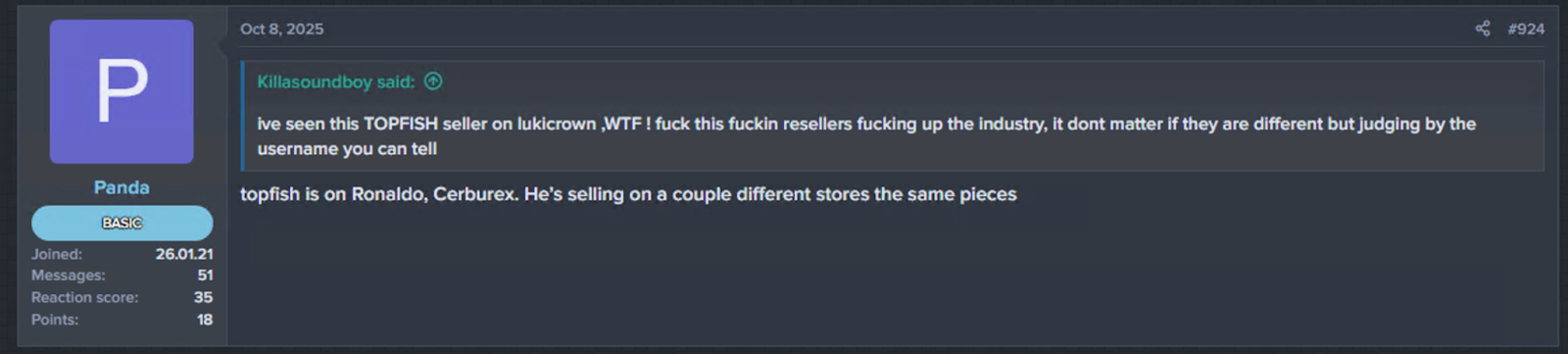

These carding marketplaces do not disclose the sources of their stolen credit card data and appear to rely primarily on third-party vendors offering previously compromised records. This suggests that they operate as aggregators, reselling data obtained from multiple external suppliers after conducting their own quality assessments. While this model enables platforms to increase both the volume and diversity of their listings, it can also lead to inconsistencies in data quality. Additionally, some resellers appear to offer identical datasets across multiple marketplaces to maximize profits, resulting in overlapping bases between platforms (Figure 5).

⠀

⠀

All three marketplaces support Bitcoin payments, while Findsome is currently the only platform that accepts additional cryptocurrencies, including Litecoin and Zcash. Minimum deposit requirements are generally low, ranging from $0 on UltimateShop to $20 on Brian’s Club, likely to reduce barriers to entry and attract new users. In parallel, Findsome and UltimateShop offer deposit bonuses, typically between 5% and 12%, to incentivize larger payments and encourage long-term user engagement.

These marketplaces are hosted on the dark web, with mirrored versions accessible via the surface web. To mitigate the risk of takedowns or law enforcement action, administrators frequently rotate their surface-web domains. This practice has likely contributed to the proliferation of fraudulent domains impersonating legitimate marketplaces, such as findsome[.]ink and findsomes[.]ru for Findsome, and ultimateshops[.]to for UltimateShop. These sites are designed to leverage brand recognition to deceive users and steal funds. In response, the marketplaces publish lists of their official domains and warn users about potential scams in an effort to maintain trust and protect their reputations.

Findsome

Findsome is a deep and dark web carding marketplace that has reportedly been active since 2019. The platform, whose administrators are likely of Russian origin, appears to specialize in the sale of stolen CVV, as well as Fullz. Listings are typically priced between $4 and $25 per record, depending on the perceived “quality” of the data.

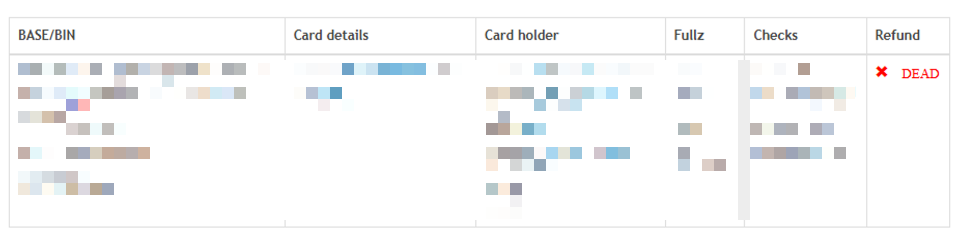

Under its “Shop” tab, Findsome enables users to browse and filter available credit card listings of interest (Figure 6). Each listing specifies whether a refund is available should the card prove to be invalid, along with a defined “check time.” The check time refers to a limited window following purchase during which the buyer may attempt to verify the card’s validity and request a refund if necessary.

⠀

⠀

During the designated check-time window, users may attempt to validate the purchased record. The marketplace claims to integrate third-party checker services, such as Luxchecker, which it describes as commonly used across comparable platforms. If the validation process indicates that the card is not valid, a refund is reportedly issued (Figure 7).

⠀

⠀

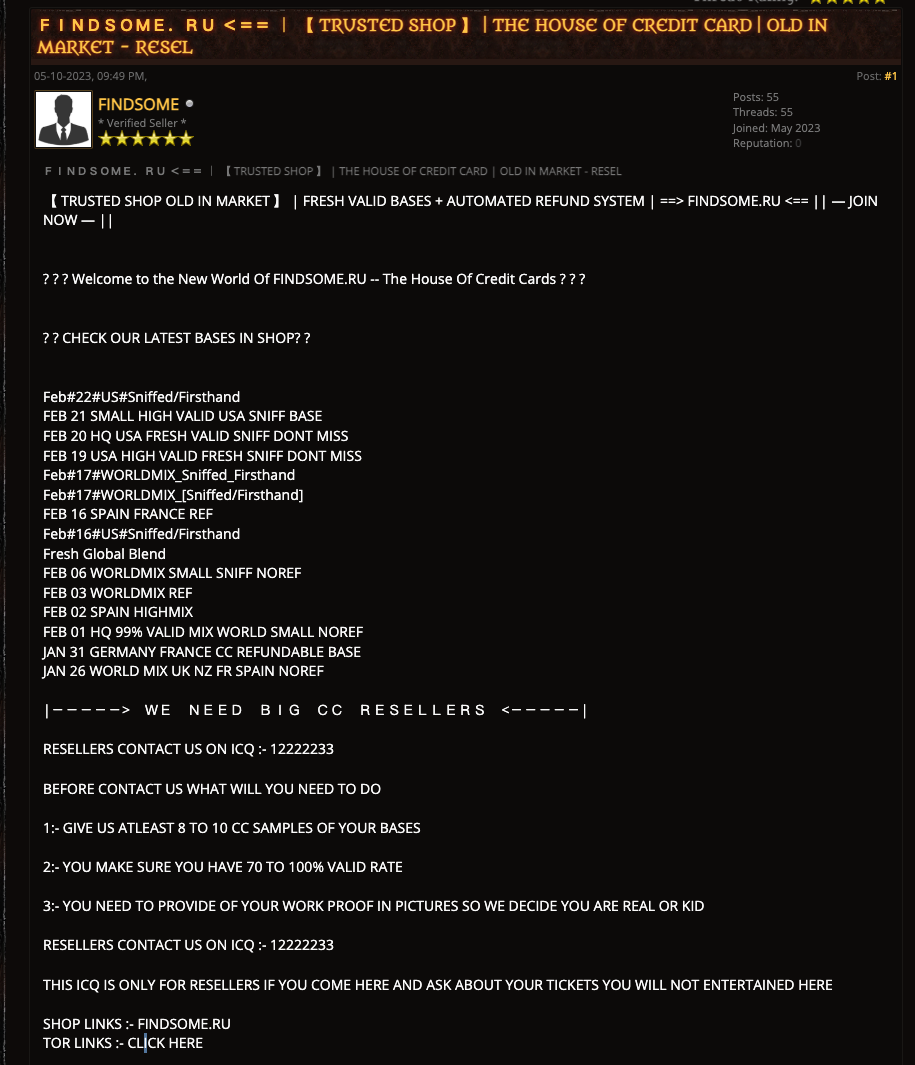

Actors associated with the marketplace have been observed seeking “resellers” offering large bases on cybercrime forums (Figure 8). Although Findsome does not explicitly disclose information about its resellers, their aliases appear to be embedded in the naming conventions of the databases. For instance, a database titled “NOV 23 _#(KOJO***) GOOD US JP SE” suggests that it was supplied by a reseller operating under the alias “KOJO***.”

⠀

⠀

An analysis of the databases published during the second half of 2025 identified the five most frequent resellers in that period (Table 1). These resellers largely dominated Findsome’s inventory, collectively accounting for more than 50% of its offerings. Overall, 51 resellers were active on the platform during this timeframe, with an average market share of approximately 2% per reseller. This distribution suggests that Findsome relies on a broad network of resellers, likely to diversify its listings and reduce dependence on a small number of dominant suppliers.

⠀

|

Reseller |

Records |

Share |

|

tian***** |

303,818 |

13% |

|

vygg******* |

266,382 |

11% |

|

mapk** |

231,797 |

10% |

|

atla**** |

231,757 |

10% |

|

find***** |

217,846 |

9% |

Table 1 – Reseller market share

⠀

Despite its prominence, Findsome appears to face competition from smaller, emerging platforms. While it is sometimes described within cybercrime communities as relatively “reliable,” discussions on underground forums reveal dissatisfaction with its pricing model. Some actors have criticized the marketplace for charging high prices for data that is frequently invalid (Figure 9), while others view the $100 account activation fee for new users as a significant barrier to entry.

⠀

UltimateShop

UltimateShop is a deep and dark web carding marketplace that has been active since at least 2022. Its administrators appear to be of Russian origin and offer mainly CVV and Fullz. The stolen credit cards are priced between $10 and $30 per record, depending on the assessed “quality” of the data.

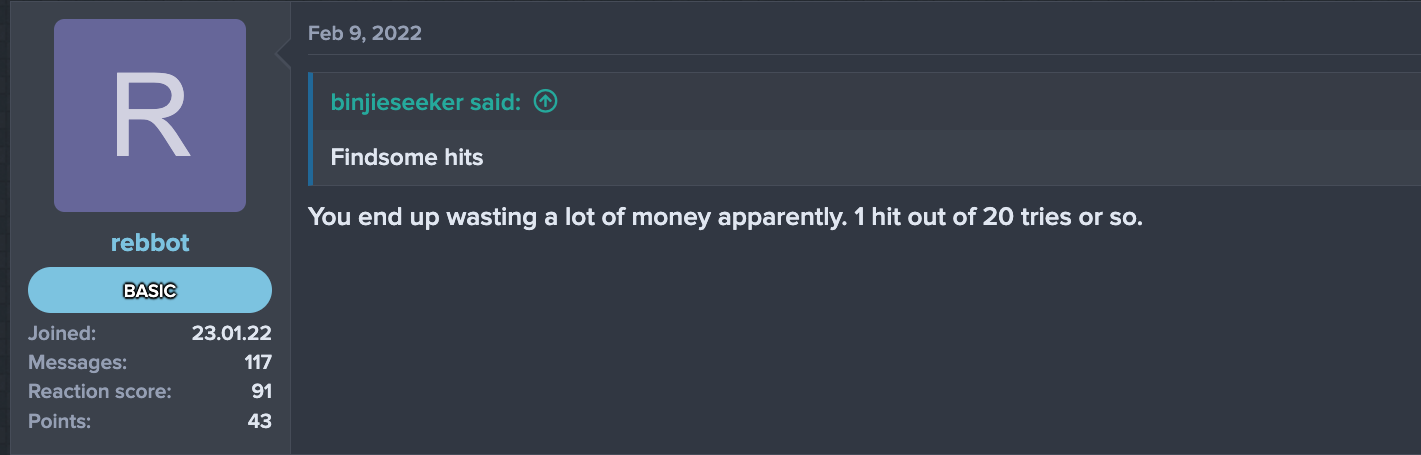

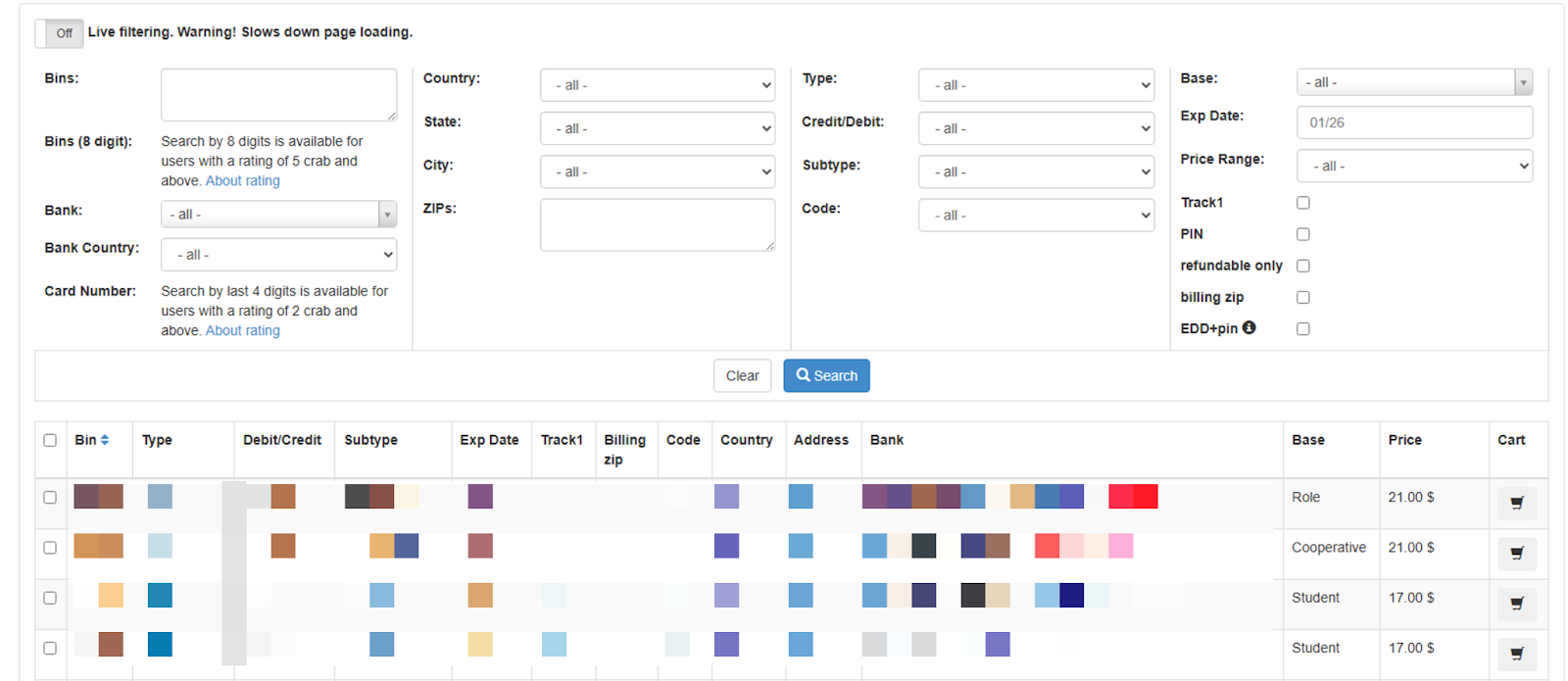

Under its “Search CCS” tab, UltimateShop allows users to filter and browse available credit card listings (Figure 10). In addition to standard filters such as BIN and issuing bank, the platform enables users to specify a price range, select individual sellers, and limit results to listings for which validation is available. The results section displays key details about the issuing bank and cardholder, as well as the seller’s name, an assessed validity percentage, and refund eligibility. It should be noted that certain BINs and issuing banks are excluded from validation checks on UltimateShop.

⠀

⠀

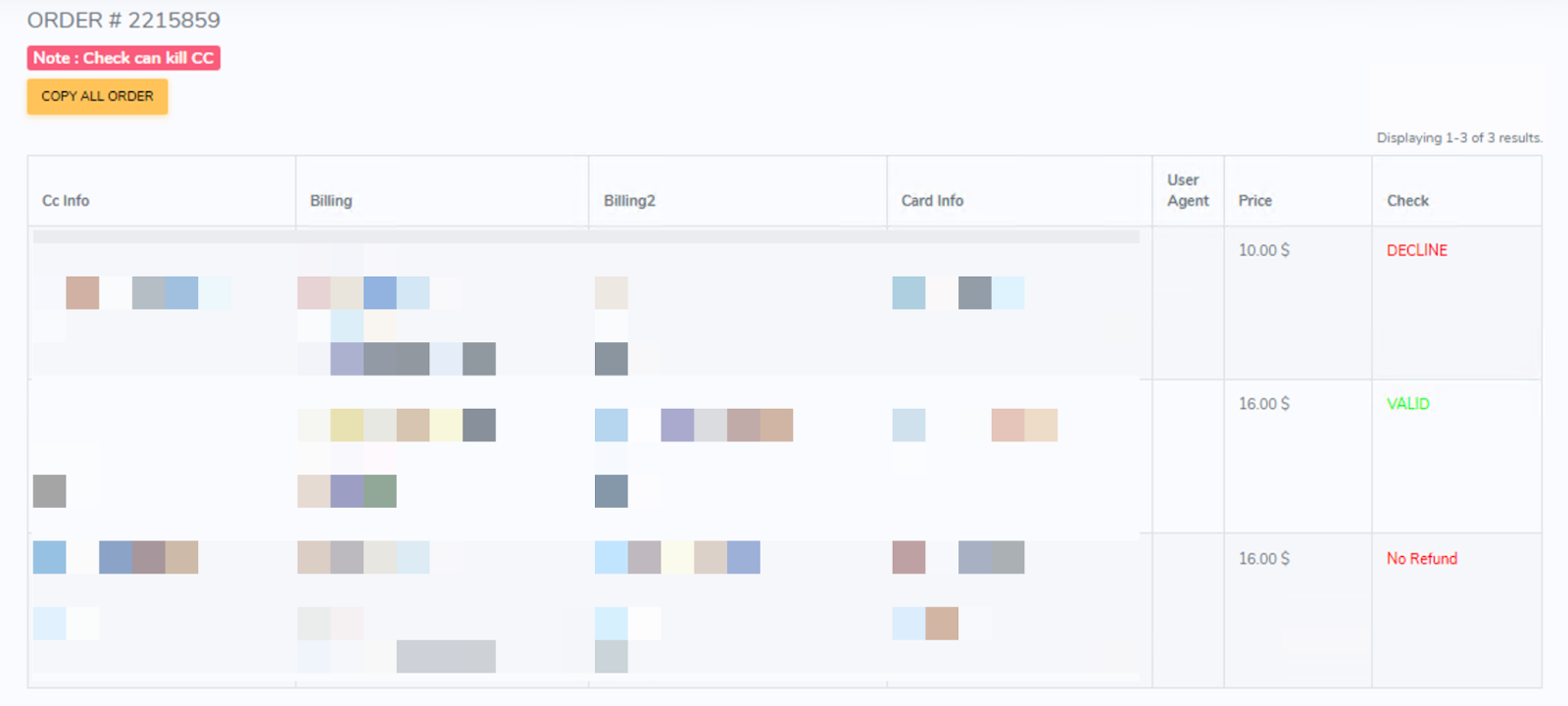

While purchasing a record, users may initiate a validation check where applicable (Figure 11). UltimateShop does not impose a strict timeframe for this process and does not disclose the checker or validation mechanism used. If the card is deemed invalid (e.g., marked as “Decline”), the user is eligible for a refund.

⠀

⠀

UltimateShop’s inventory is largely dominated by a small number of resellers, which collectively accounted for 76% of the platform’s largest offerings during the second half of 2025 (Table 2). SuperUSA appears to be the most prominent seller, contributing approximately 35% of all available records. This concentration indicates a higher reliance on a limited set of resellers and comparatively lower diversification than competing marketplaces such as Findsome. In total, 22 primary resellers were identified on UltimateShop, with an average market share of approximately 5% per reseller.

⠀

|

Reseller |

Records |

Share |

|

superusa |

293,931 |

35% |

|

best |

116,464 |

14% |

|

virgin |

82,672 |

10% |

|

sanji |

79,110 |

9% |

|

freshsniffer |

62,760 |

8% |

Table 2 – Reseller market share on UltimateShop

⠀

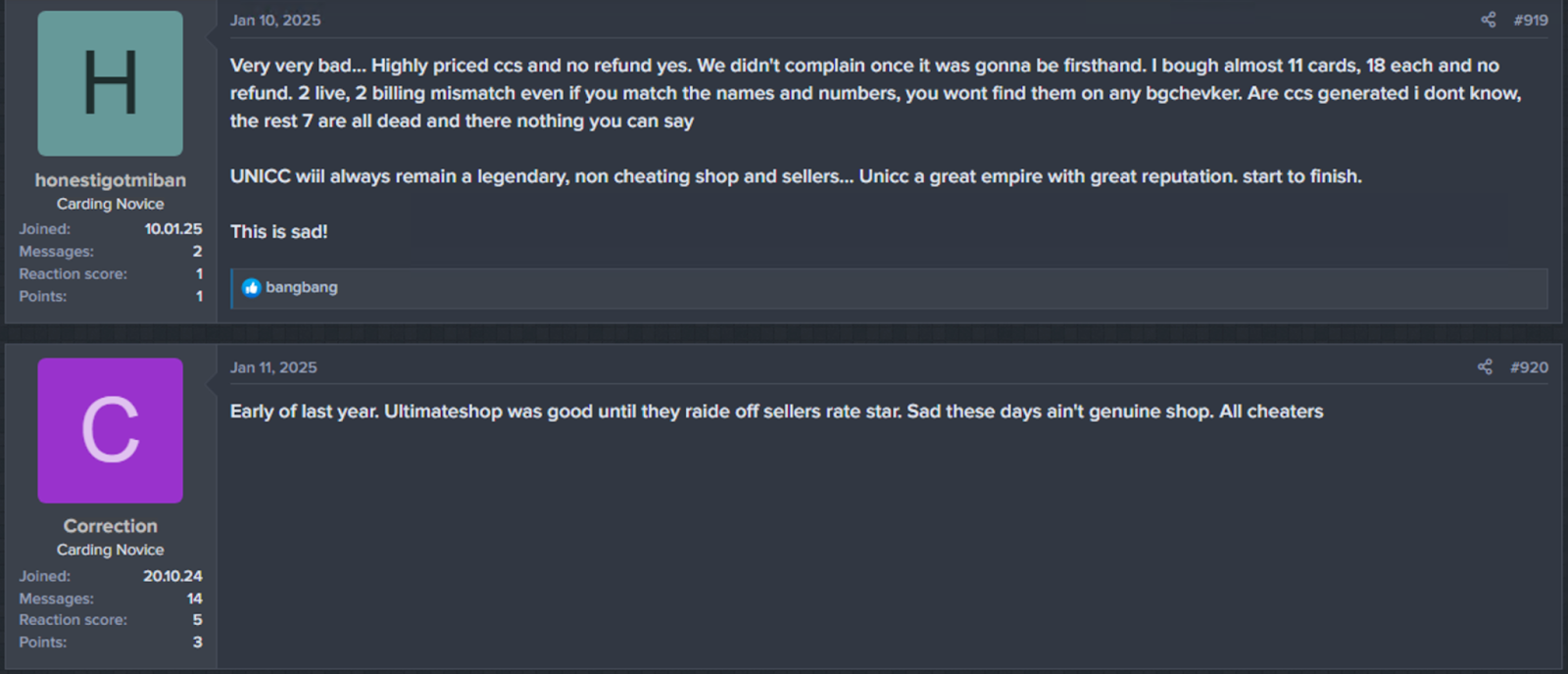

While UltimateShop remains a well-established platform within the carding ecosystem, its reputation is increasingly being challenged by negative user feedback. Complaints frequently cite high prices and a significant proportion of invalid records, issues that may stem from the platform’s reliance on a small number of potentially unreliable sellers (Figure 12).

⠀

Brian’s Club

Active since 2014, Brian’s Club is a well-established player within the carding ecosystem that was originally created to “troll” security researcher and reporter Brian Krebs and his work. Like other marketplaces, it offers a wide range of listings, categorized as “CVV2,” “Dumps,” and “Fullz” (Figure 13). Prices typically range from $17 to $49, though higher prices are often observed for records that include PINs, an uncommon feature among carding marketplaces.

⠀

⠀

Another key point of differentiation for Brian’s Club is its extensive offering of dumps, suggesting explicit support for credit card cloning. This is further reinforced by the availability of a “Track1 Generator” tool, which facilitates the creation of physical copies of compromised cards (Figure 14). Together, these features represent a relatively unique value proposition within the carding market and indicate that Brian’s Club administrators have deliberately positioned the platform to address specific customer needs and prevailing market dynamics.

General statistics

Note: The data in this section, specifically the numerical figures, comes directly from the marketplaces and, therefore, its precision cannot be independently verified or guaranteed.

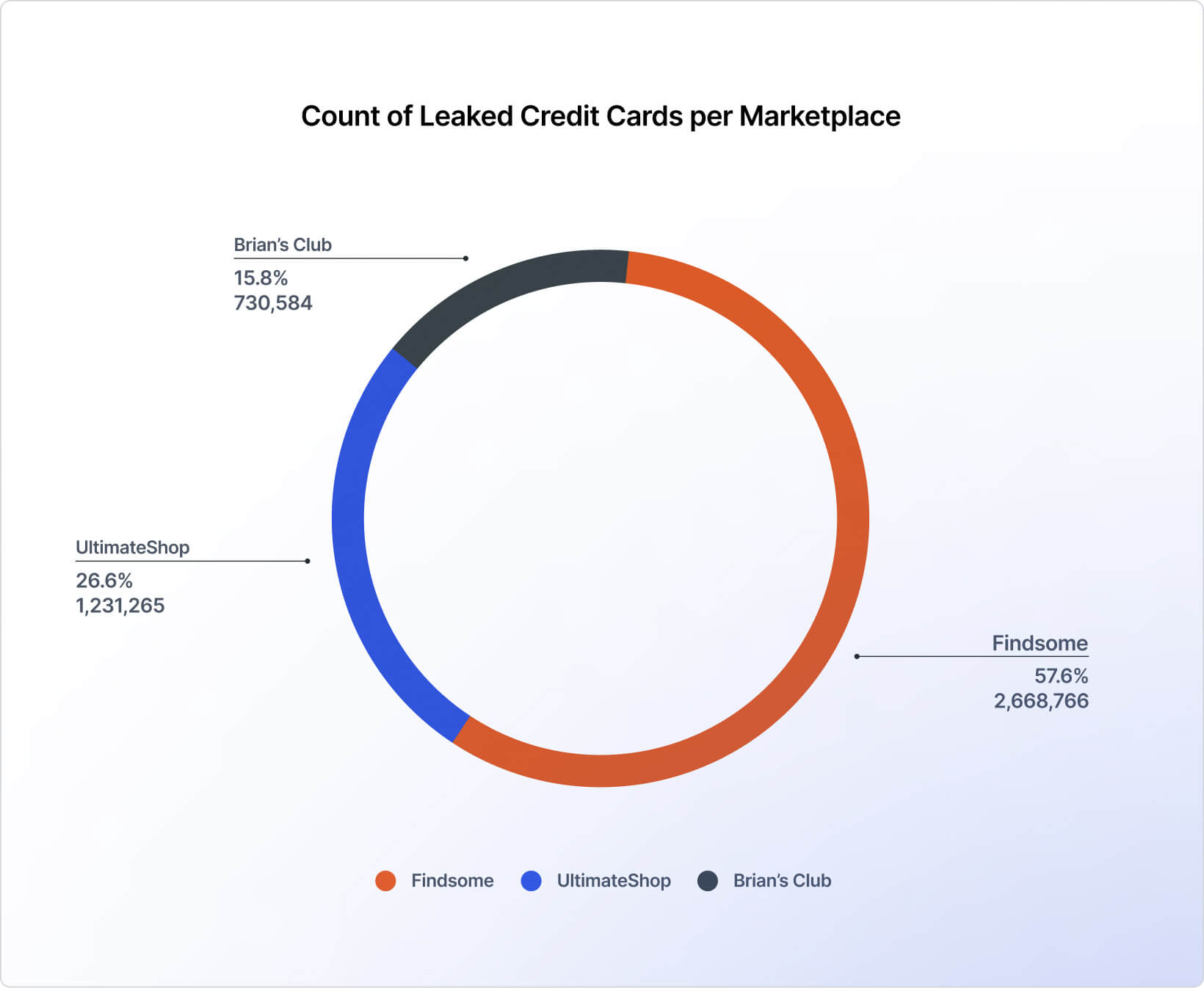

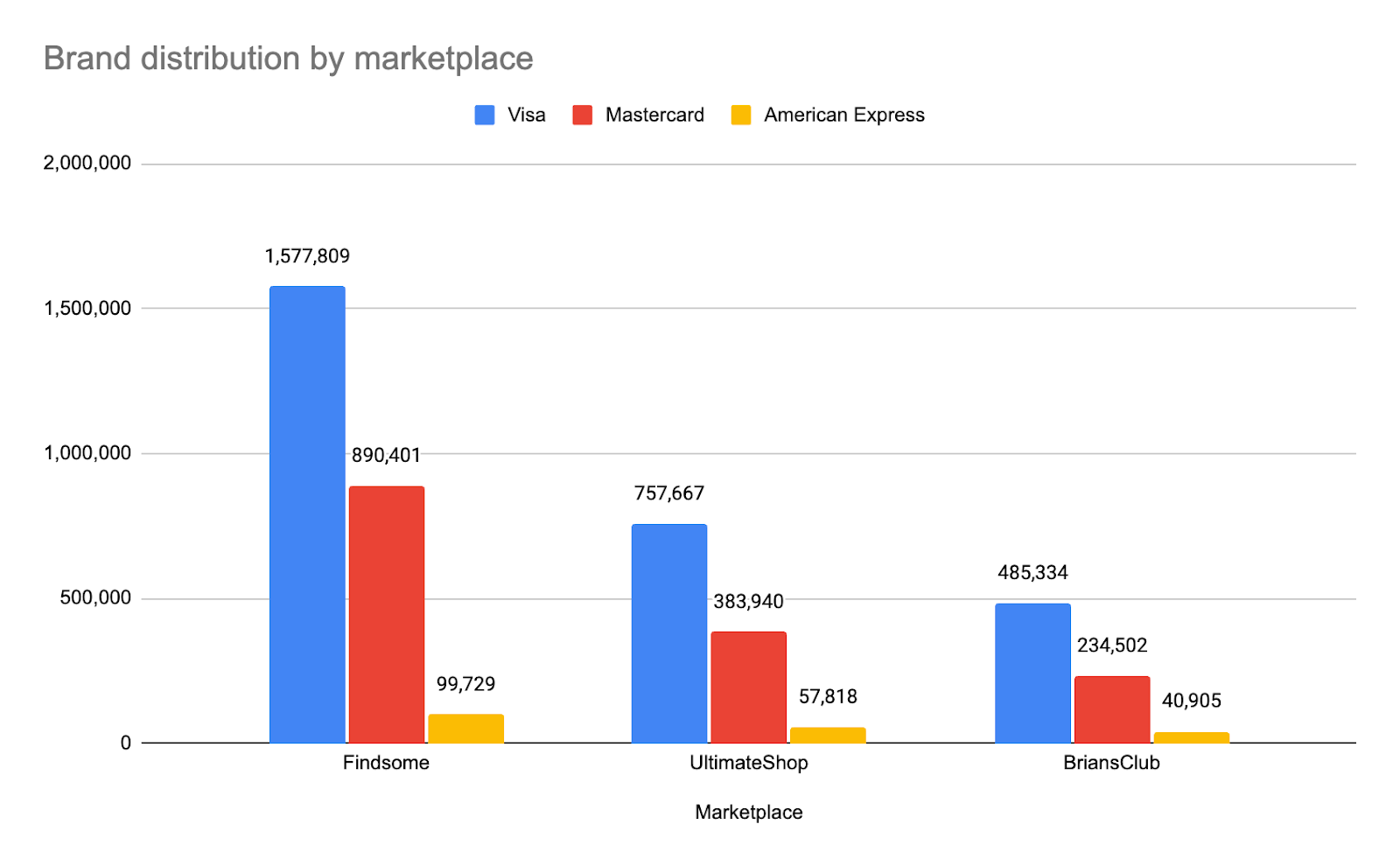

Out of the examined marketplaces, Findsome has the largest market size with 57.6%, followed by UltimateShop (26.6%) and Brian’s Club (15.8%) (Figure 14).

⠀

⠀

The vast majority of leaked credit cards are Visa cards (60.4%), followed by Mastercard (32.3%), American Express (4.3%), and Discover (3%), with this distribution remaining consistent across the three examined marketplaces (Figure 15). These numbers, however, do not reflect the actual market size of each brand, as according to the 2025 Nilson Report, Visa and Mastercard control relatively similar market sizes, with 32% and 24%, respectively, and American Express and Discover are far behind with 6% and 0.9%. In addition, the most popular credit card brand, Union Pay, with 36% of the market, is not even among the top 4 most leaked brands, probably due to its relatively unique target audience (China), which is not typically targeted by carders in these marketplaces.

However, the leaked credit cards’ brand distribution more closely resembles their market share in the United States (Visa – 52%, Mastercard – 24%, American Express – 19%, Discover – 5%), which is where most of the victims originate.

⠀

⠀

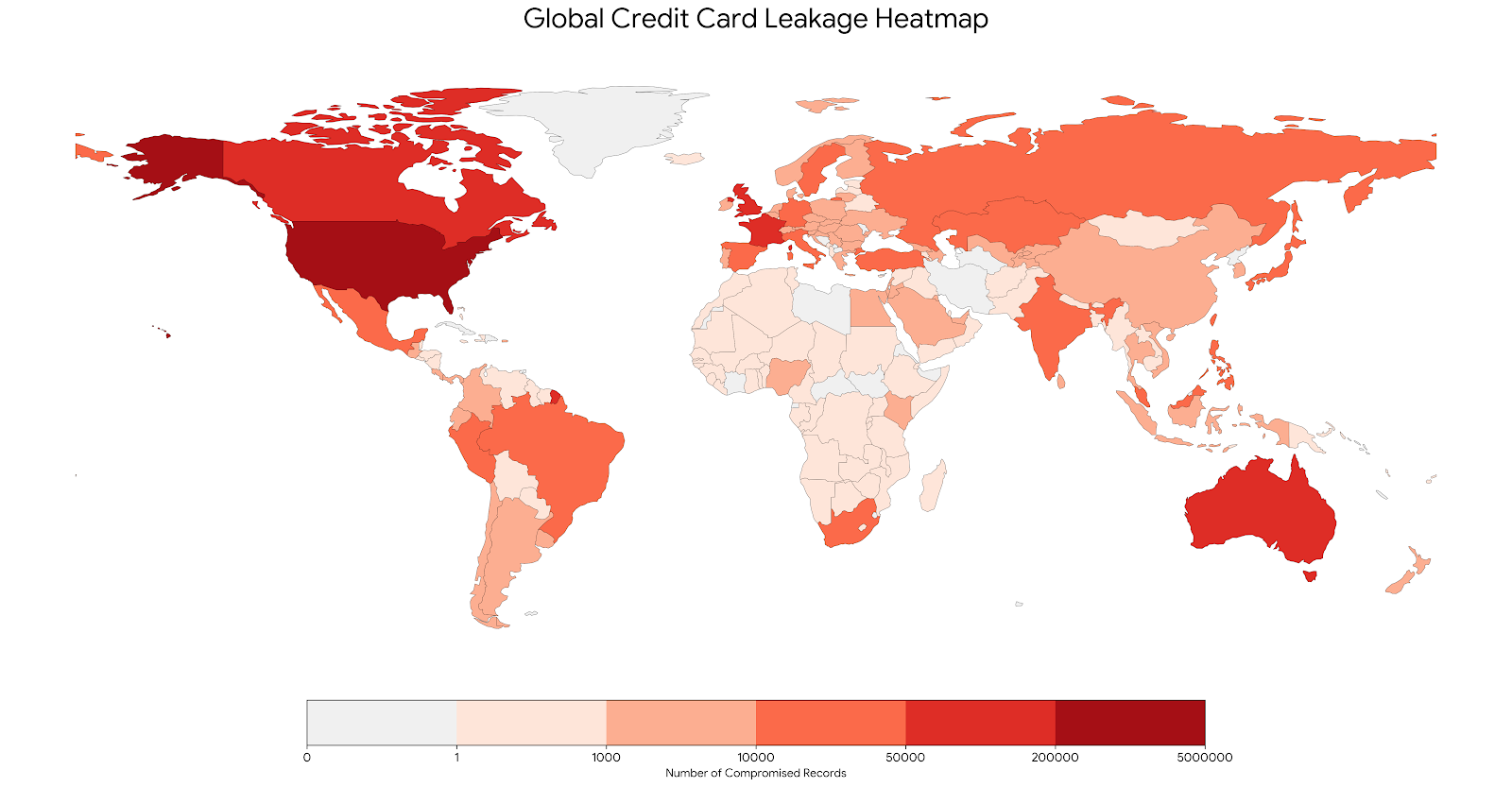

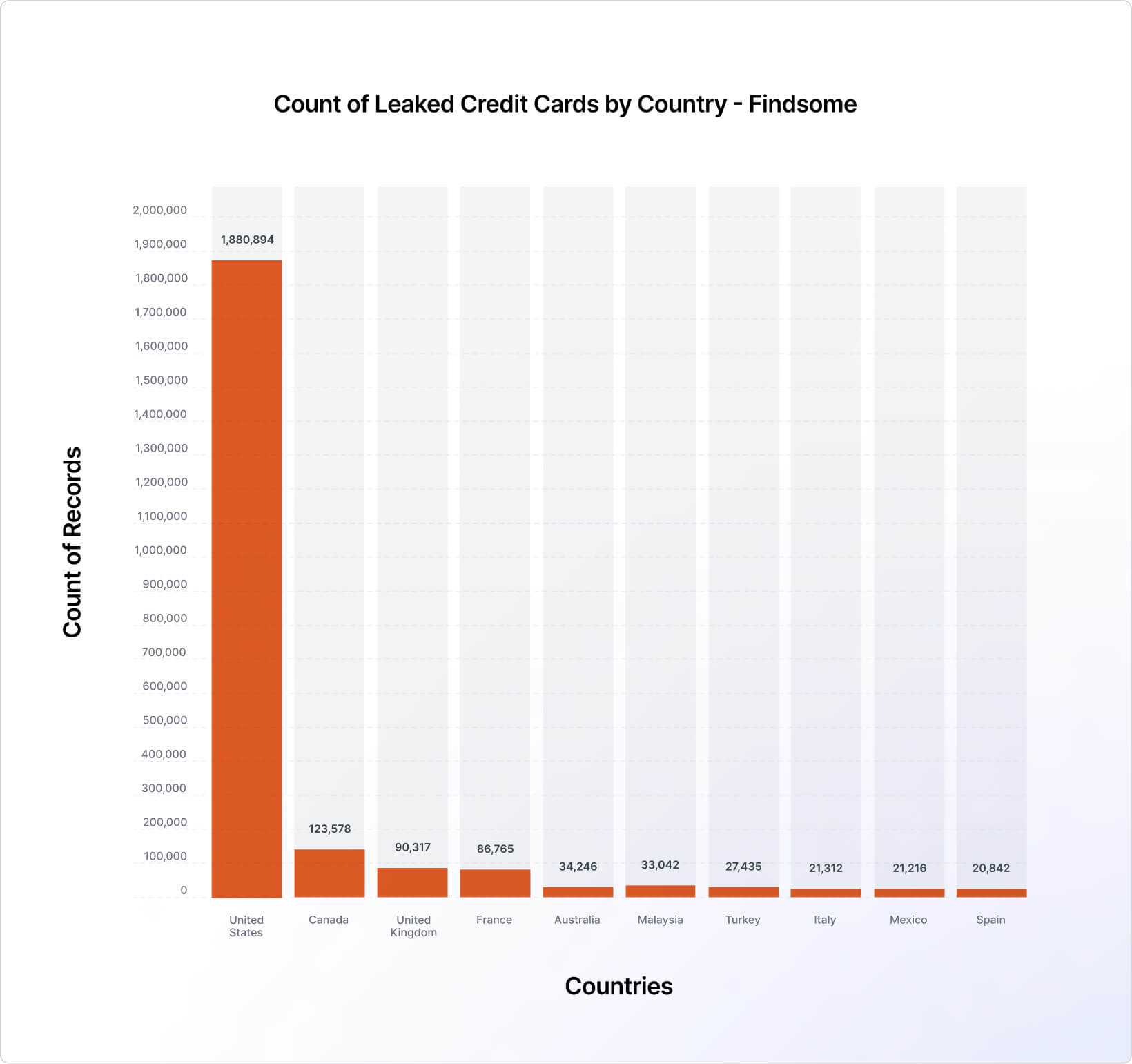

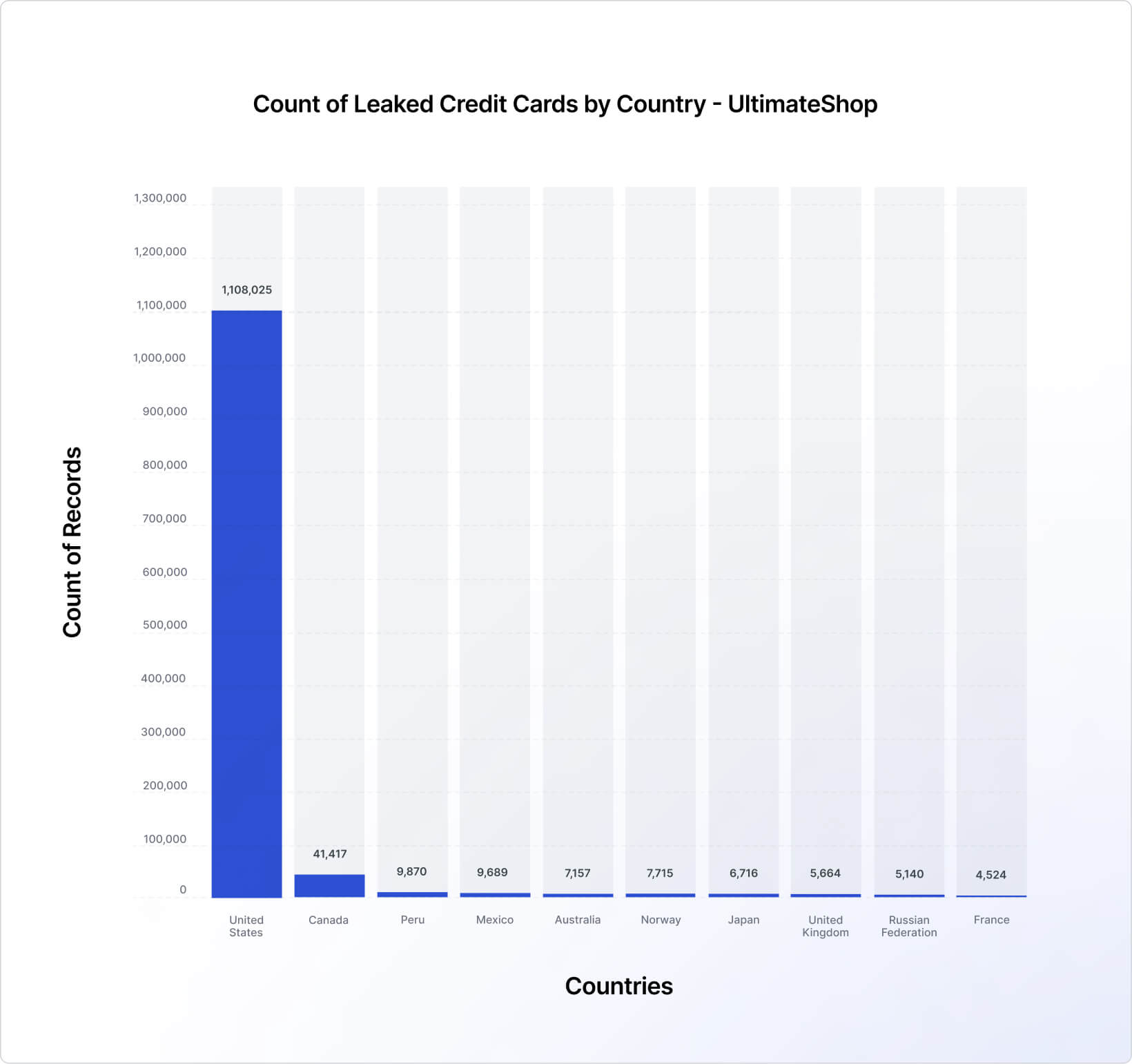

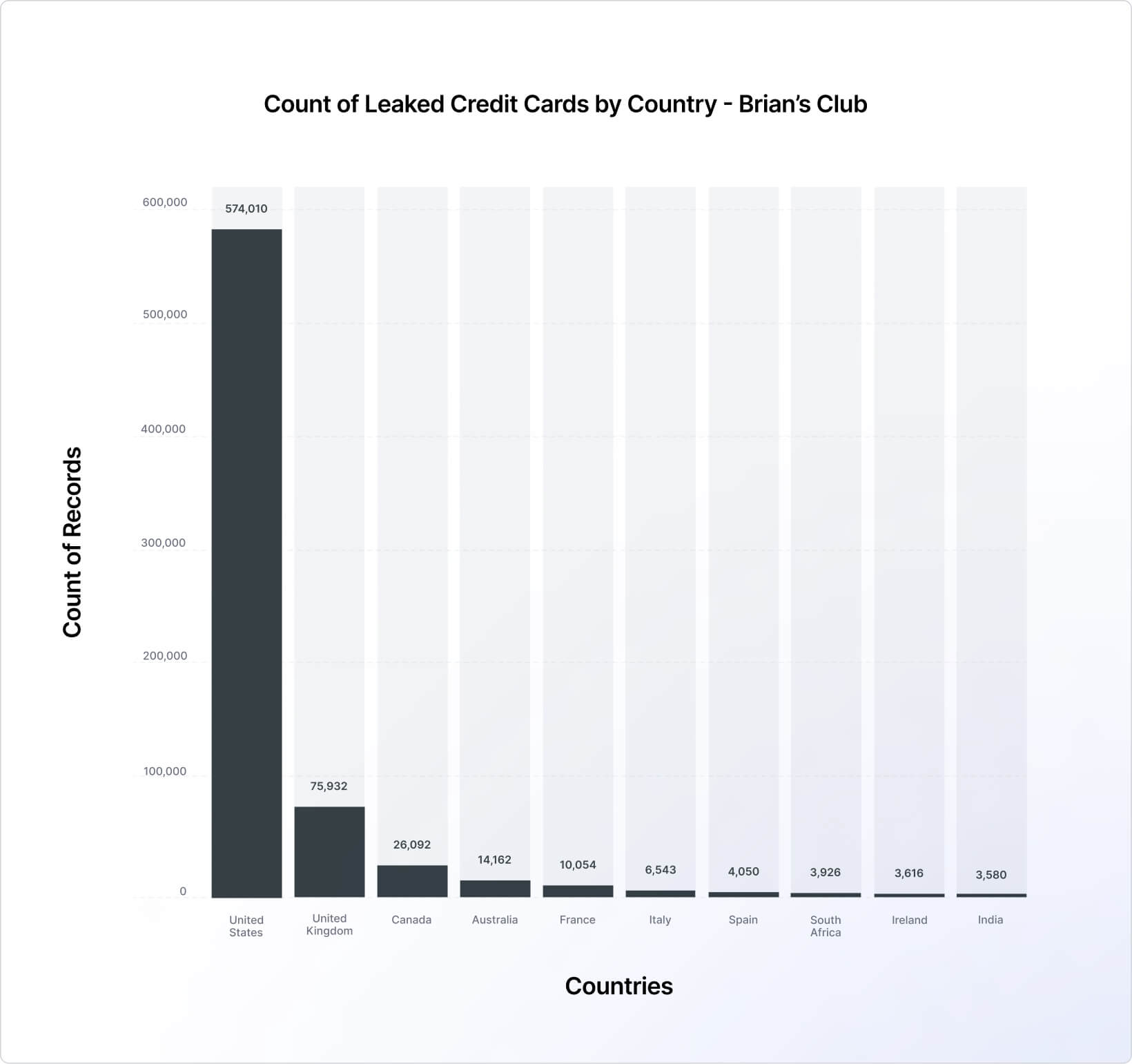

Most of the leaked credit cards we observed in H2 2025 belong to US customers, followed by ones from Canada (by a large margin) and the United Kingdom (Figure 16).

⠀

⠀

When comparing the top 10 countries list of each of the examined marketplaces (Figures 17, 18, and 19), we can see that UltimateShop’s list is somewhat unusual, with rarely targeted countries, like Peru and Norway, making the Top 10 list while surpassing very populated and highly targeted countries, such as the United Kingdom and France. In this sense, it should be noted that the geographic data sourced from UltimateShop contained numerous inconsistencies. Thus, it may not be a reliable indicator of the actual distribution of victims.

⠀

⠀

⠀

⠀

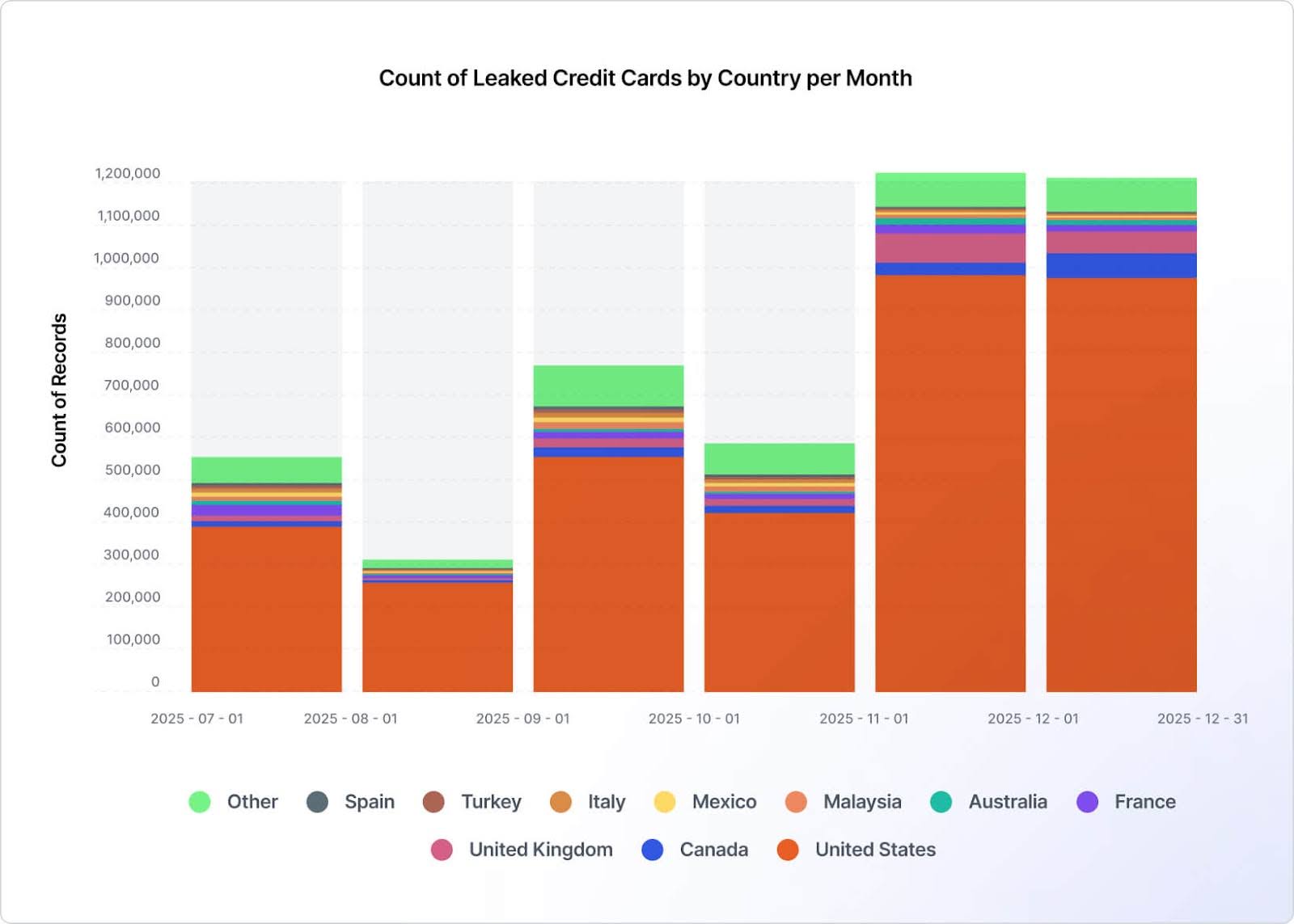

When examining the monthly distribution of leaked credit cards (Figure 20), we observe that the largest volume was recorded in November and December, likely due to the shopping season (e.g., Black Friday and Cyber Monday) that occurs around that time.

⠀

⠀

When examining the types of personal information being exposed along with the leaked credit card, we saw that most of the credit cards are also attached with an email address or a phone number (or both), with the highest percentages recorded in UltimateShop (99.4% of the cases), followed by Findsome (87.7%), and Brian’s Club (75.7%). This means that the leakage of a credit card not only poses a risk for financial scams resulting in monetary losses, but also exposes PII, which may lead to identity theft and impersonation attempts.

The future of carding

The carding ecosystem is gradually moving away from large-scale magnetic stripe (“dump”) fraud as EMV adoption makes card cloning harder and less reliable. While shimming and the capture of PINs allow criminals to continue card-present fraud, this approach is riskier, more expensive, and usually limited to specific regions or devices. As a result, EMV-based fraud is unlikely to fully replace the dump economy at scale. Instead, it is expected to support smaller, localized operations rather than the global, highly automated carding marketplaces that dominated in the past.

At the same time, carding marketplaces are increasingly focused on selling richer data sets that include personal and contact information (“Fullz”), not just card details. This shift enables a wider range of fraud, including account takeover, wallet abuse, phishing, and identity-based scams, which are less dependent on the underlying payment technology. Rather than disappearing, carding-as-a-service is evolving into a broader identity-driven ecosystem, where marketplaces supply raw data, and buyers use automation and AI to decide how and where to exploit it.

What organizations should do

The continued growth of carding marketplaces highlights how credit card theft has evolved into a resilient, service-based criminal economy that is difficult to disrupt through takedowns alone. In addition, as stolen cards are increasingly bundled with credentials and personal data, the potential damage inflicted by the CaaS economy has ceased to be purely financial. The impact extends beyond isolated fraud events to long-term identity abuse and account compromise affecting both organizations and consumers.

To cope with the growing threat of stolen credit cards and leaked credentials, organizations should adopt a defense-in-depth approach that combines prevention, detection, and rapid response. This includes strengthening protections against common compromise vectors such as phishing, malware, and web application vulnerabilities by enforcing multi-factor authentication, regularly patching systems, hardening payment pages against client-side attacks, and conducting ongoing security awareness training. At the same time, organizations should invest in continuous monitoring capabilities to detect early signs of exposure, including visibility into dark web and underground marketplaces where stolen card data and credentials are traded.

By proactively identifying leaked assets, correlating them to their own environments (for example, through BIN monitoring), and responding quickly through card reissuance, credential resets, and fraud monitoring, organizations can significantly reduce both financial losses and downstream risks such as identity theft and account takeover.

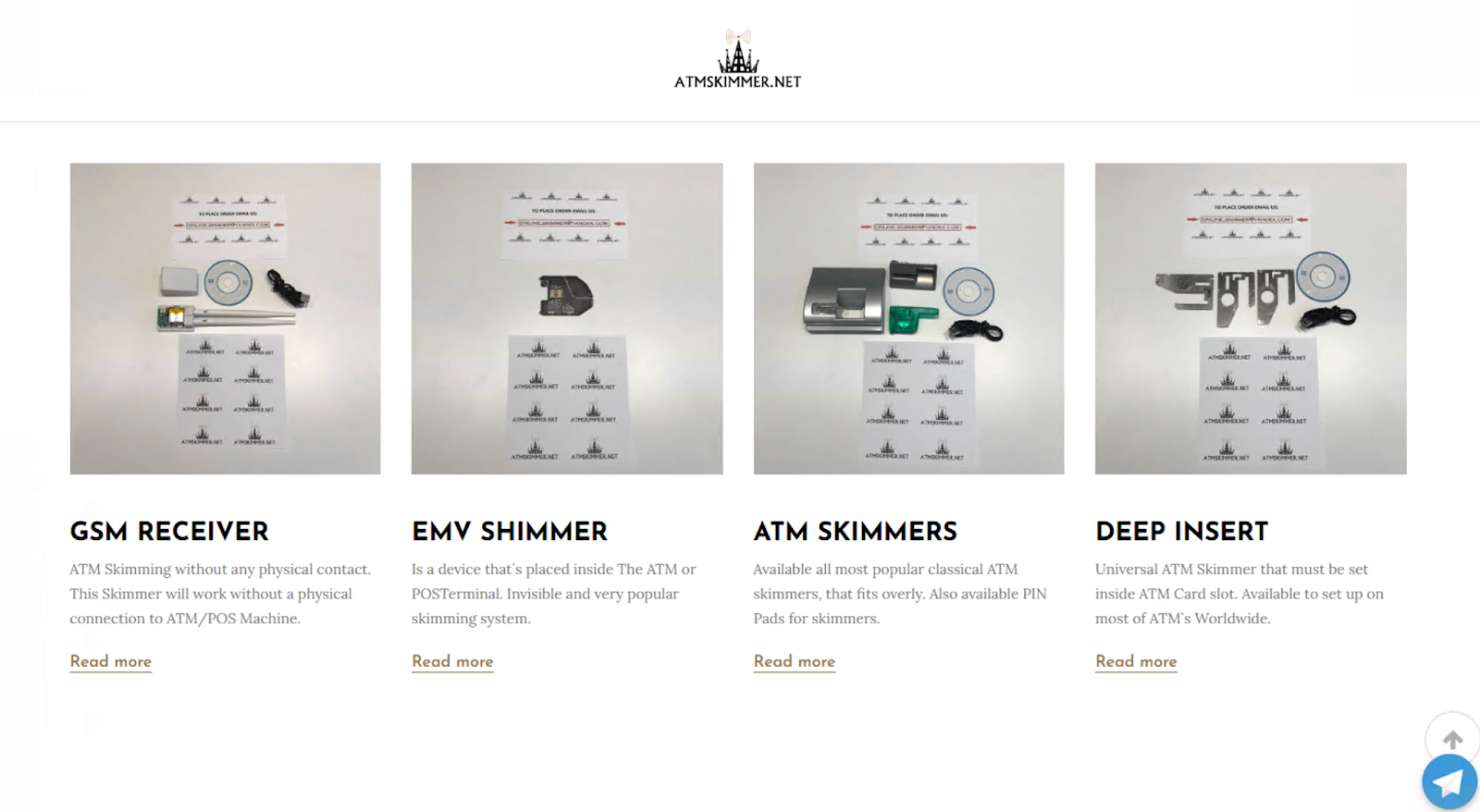

Rapid7 customers

There are multiple detections in place for Threat Command and MDRP customers to identify and alert on the threat actor behaviors described in this blog. Specifically, Threat Command monitors dark web activity, including exposed credit card details that are being sold on carding marketplaces. Relevant incidents are flagged based on the customer’s assets, specifically their BIN. When a listing containing these assets is identified, a “Credit Cards For Sale” alert is issued (Figure 21). In addition to notifying customers, these alerts enable them to quickly and securely acquire the detected bot through the “Ask an Analyst” service.

⠀